Oppenheimer, una bomba chiamata Trinità

Bettmann Archive / Getty Images

Il 16 luglio 1945 venne fatta esplodere la prima bomba nucleare della storia. Il test fu eseguito alle 5 e mezza del mattino nel deserto del New Messico, negli Stati Uniti d’America.

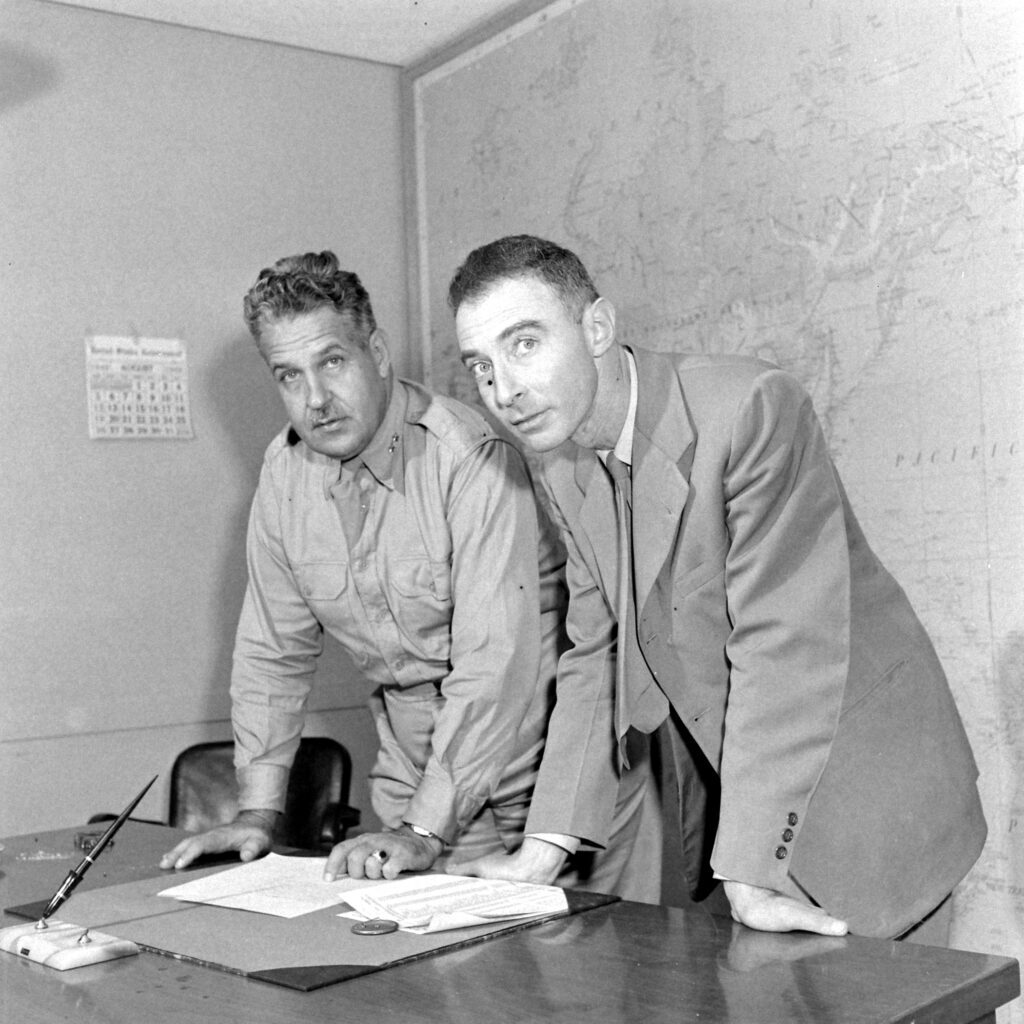

Il nome in codice del test, Trinity, fu assegnato da Julius Robert Oppenheimer che era a capo del Progetto Manhattan: una poesia di John Donne che richiamava la Trinità diede il nome a quella che sarebbe diventata la più potente arma di distruzione di massa costruita dall’uomo.

Fu lo stesso Oppenheimer a spiegare in una lettera il perché di quella scelta al generale Leslie Groves, responsabile militare del progetto: “Perché ho scelto il nome non è chiaro, ma – scrive – so quali pensieri avevo in mente. C’è una poesia di John Donne, scritta poco prima della sua morte, che conosco e amo, su un uomo che non ha paura di morire perché credeva nella resurrezione: “Hymn to God, My God, in My Sickness”.

Marie Hansen/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Hymn to God, My God, in My Sickness

John Donne

Since I am coming to that holy room,

Where, with thy choir of saints for evermore,

I shall be made thy music; as I come

I tune the instrument here at the door,

And what I must do then, think here before.

Whilst my physicians by their love are grown

Cosmographers, and I their map, who lie

Flat on this bed, that by them may be shown

That this is my south-west discovery,

Per fretum febris, by these straits to die,

I joy, that in these straits I see my west;

For, though their currents yield return to none,

What shall my west hurt me? As west and east

In all flat maps (and I am one) are one,

So death doth touch the resurrection.

Is the Pacific Sea my home? Or are

The eastern riches? Is Jerusalem?

Anyan, and Magellan, and Gibraltar,

All straits, and none but straits, are ways to them,

Whether where Japhet dwelt, or Cham, or Shem.

We think that Paradise and Calvary,

Christ’s cross, and Adam’s tree, stood in one place;

Look, Lord, and find both Adams met in me;

As the first Adam’s sweat surrounds my face,

May the last Adam’s blood my soul embrace.

So, in his purple wrapp’d, receive me, Lord;

By these his thorns, give me his other crown;

And as to others’ souls I preach’d thy word,

Be this my text, my sermon to mine own: “Therefore that he may raise, the Lord throws down.”

Continuando nella sua lettera, Oppenheimer racconta che il richiamo alla Trinità, in particolare, è in un altro poema di Donne:

Holy Sonnets: Batter my heart, three-person’d God

John Donne

Batter my heart, three-person’d God, for you

As yet but knock, breathe, shine, and seek to mend;

That I may rise and stand, o’erthrow me, and bend

Your force to break, blow, burn, and make me new.

I, like an usurp’d town to another due,

Labor to admit you, but oh, to no end;

Reason, your viceroy in me, me should defend,

But is captiv’d, and proves weak or untrue.

Yet dearly I love you, and would be lov’d fain,

But am betroth’d unto your enemy;

Divorce me, untie or break that knot again,

Take me to you, imprison me, for I,

Except you enthrall me, never shall be free,

Nor ever chaste, except you ravish me.

E mentre l’uomo stava ultimando l’arma finale, quello stesso uomo era attraversato da pensieri e sensazioni alimentati anche dagli scrittori più amati e dai libri che lo avevano segnato per una vita intera. Uno di questi, un testo sacro per l’induismo, la “Bhagavad-Gita”, lo spinse perfino a studiare una lingua antica, il sanscrito. Fu talmente colpito da questo libro che regalò negli anni a venire ad amici e colleghi la traduzione in inglese curata da Arthur W. Ryder.

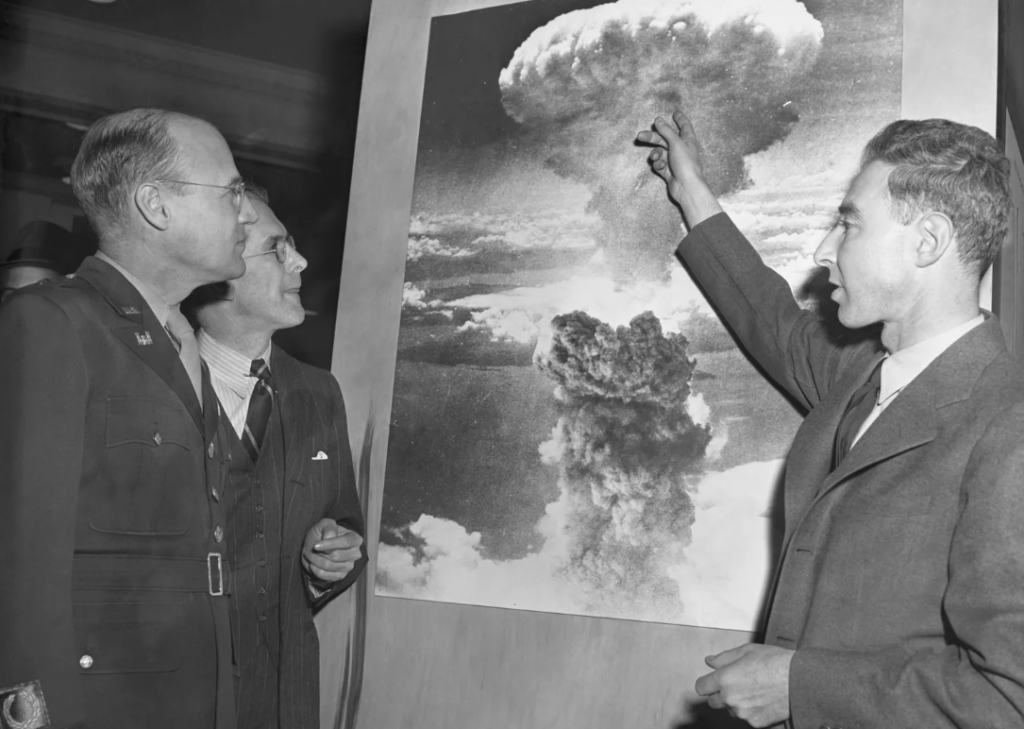

Preparandosi a Trinity, i pensieri di Oppenheimer erano tutti indirizzati al successo del test ma anche all’impatto che la bomba avrebbe avuto sulla vita del mondo intero.

Vannevar Bush, direttore dell’Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD) e presidente del National Defense Research Committee (NDRC), in un suo libro di memorie riporta una poesia tradotta da Oppenheimer dal sanscrito che lo scienziato gli recitò due sere prima del test nucleare:

In battle, in forest, at the precipice in the mountains,

On the dark great sea, in the midst of javelins and arrows,

In sleep, in confusion, in the depths of shame,

The good deeds a man has done before defend him”

Secondo Oppenheimer era dovere degli scienziati costruire la bomba, ma era dovere dello statista decidere se e come usarla.

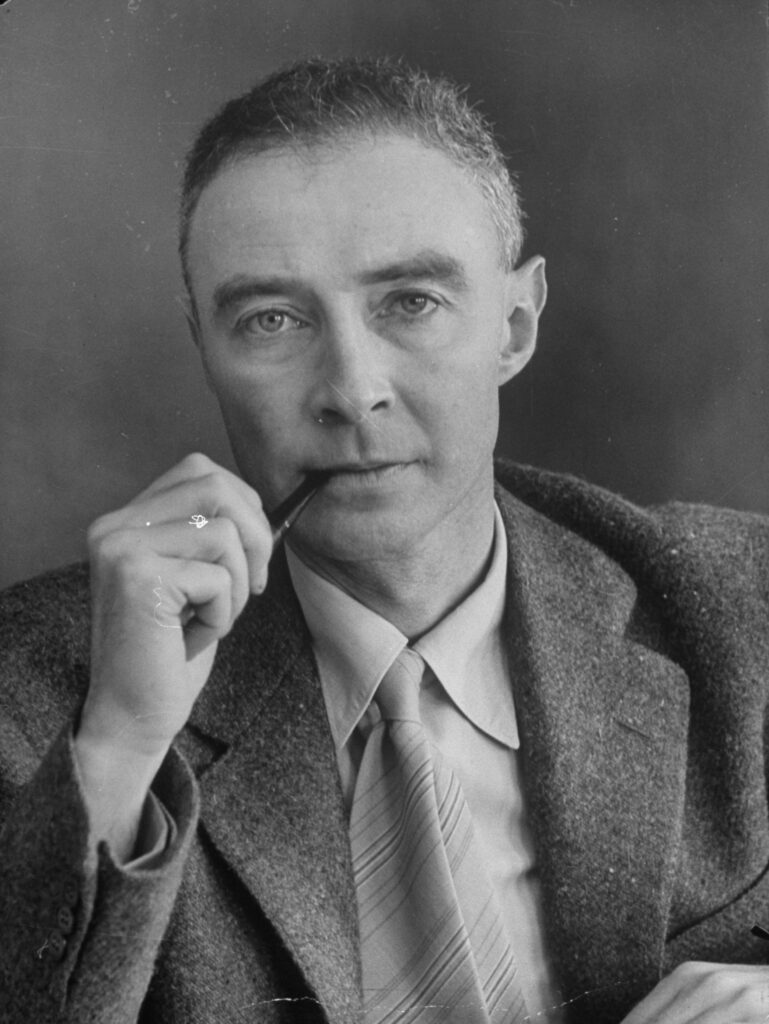

Il fisico americano citava regolarmente la “Bhagavad-Gita”, in particolare, dopo aver visto la detonazione si racconta che pronunciò la frase: “Ora sono diventato Morte, il distruttore di mondi”.

Il verso in questione è tratto dal capitolo 11, verso 32, in cui la divinità Krishna rivela la sua forma divina al guerriero Arjuna. Assistendo alla terrificante vista della forma cosmica di Krishna, Arjuna è sopraffatto dalla soggezione e dalla paura.

L’immensa distruzione scatenata dalla bomba atomica rese Oppenheimer profondamente consapevole del potenziale devastante delle armi nucleari e l’uso di quella citazione riflette la sua introspezione sulle conseguenze del suo lavoro e la responsabilità morale che ne derivava.

Era lui dunque in quel momento il distruttore di mondi? Secondo l’interpretazione dello storico Alex Wellerstein, “Oppenheimer non è Krishna/Vishnu, non il terribile dio, non il ‘distruttore di mondi’: è Arjuna, il principe umano! È colui che non voleva davvero uccidere i suoi fratelli, i suoi simili ma fu spinto a combattere qualcosa di più grande di lui – la fisica, la fissione, la bomba atomica, la Seconda Guerra Mondiale.

Rimane intimorito dallo spettacolo della morte svelato davanti ai suoi occhi, nel memento mori più impressionante del mondo. Spinto da qualcosa di cosmico e terrificante, Oppenheimer si riconcilia con il suo dovere di principe della fisica e quel dovere era la guerra.

Come viveva Oppenheimer le ore precedenti al test ce lo raccontano Kai Bird e Martin J. Sherwin nel libro “American Prometheus”: sorseggiando caffè a tarda notte nella mensa del campo base, fumando e leggendo Baudelaire.

Tra i poeti più amati da Oppenheimer c’è TS Eliot, chiamato in seguito a capo dello stesso Institute for Advanced Study diretto dal fisico americano. In uno dei versi di “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” c’è un passaggio emblematico:

“Do I dare

Disturb the universe?”

Alfred Eisenstaedt/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock.

Dunque Oppenheimer fu un amante della poesia ma anche scrittore e molto critico verso sé stesso: in una lettera del 1924 diretta a Herbert Smith, suo insegnante di inglese al liceo, si legge che per lui la sua scrittura non era “… pensata o adatta alla lettura di nessuno”.

Ma una poesia uscì dall’ombra e fu pubblicata nel 1928 sulla rivista “Hound & Horn”, il suo titolo era: “Crossing”

CROSSING

It was evening when we came to the river with a low moon over the desert that we had lost in the mountains, forgotten, what with the cold and the sweating and the ranges barring the sky.

And when we found it again, in the dry hills down by the river, half withered, we had the hot winds against us.

There were two palms by the landing; the yuccas were flowering; there was a light on the far shore, and tamarisks.

We waited a long time, in silence.

Then we heard the oars creaking and afterwards, I remember, the boatman called to us.

We did not look back at the mountains.

Nel 1963, a Oppenheimer fu chiesto dalla rivista “The Christian Century” quali libri avessero segnato la sua esistenza. Questo fu l’elenco, non in ordine di importanza:

“Les Fleurs du Mal (I fiori del male)” di Charles Baudelaire

“The Waste Land” di TS Eliot

“La Divina Commedia” di Dante Alighieri

“Bhagavad Gita”

“Śatakatraya” (“I tre secoli”) di Bhartrihari

Amleto di William Shakespeare

L’Éducation Sentimentale” di Gustave Flaubert

Le opere complete di Bernhard Riemann

“Teeteto” di Platone

I taccuini dello scienziato Michael Faraday

- Fingernails. Il vero amore? Sulle dita di una mano - 27 Febbraio 2024

- Dybala meglio di Goethe, il suo Inno d’amore a Roma - 26 Febbraio 2024

- Seme di libertà - 22 Gennaio 2024